Beginning this experimentation by looking back at Nancy Stark-Smith’s ‘Underscore’ enabled me to explore how this method can be used to generate connections with other performers, while also discovering how natural it feels due to her creating it based on natural observations. The idea that when you leave the score and stand around the side you are still involved in the performance was hard to grasp. This is due to me finding myself getting engrossed in the performance that is happening and I would be focusing so closely that I would forget to be readily available to respond to the piece as a whole and also the way I was presenting myself to other performers and audience members. Stark-Smith discusses how she rehearses an audience to make them receptive to her scores, “I feel a great desire to get to a point where the work is accessible in the performance” (Halprin in De Spain, 2014, 67). When in the score I felt that losing the connection mean’t that I wasnt making the piece accessible for the audience, losing Stark-Smith’s intention for her scores.

I found that this score process allowed for a high amount of exploration and composition, where if I didn’t know what to do or that the piece was becoming ‘stuck’ I could return to the earlier stages such as exploring the lower kinesphere or skinesphere or even agitating the space. The score therefore allowed for tracking back to generate a starting point which you could explore and generate into composition. I learnt that as the piece continued over time it developed and improved in terms of conscious relationships and connections being made and intentions with new ideas to form. From this I discovered that it takes a while for empathy to become tangible and awareness to others to fully open and develop. However, once it had developed there was an increase in phrasing and reaction to one another which created interesting and unique connections. Within the work everyone had very different artistic voices which I found added to the piece, as it created contrasting moments and innovative sections that with less performers or similar styled performers, may have reduced. I discovered that therefore the piece wouldn’t get stuck in one place for the whole time and was continually developing.

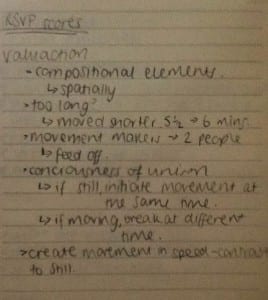

Following this, we went back and valuated our RSVP scores together as a group again to find improvements. The decisions we came up with were:

Within our work we reduced the amount or freedom and added some more structure, removing of the full freedom in movement and creating movement makers who come up with the material as we previously learnt through Thomas Lehmen’s scores. There would be two material makers and all other performers would interpret the movement they generate and in stillness would stop to observe the performance to decide what was needed and what we could add. I discovered that by doing this there would be more coherence throughout the movement across performers so that a group relationship and stronger connections could be built.

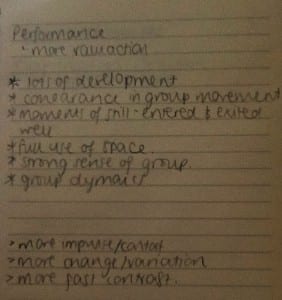

We then re-performed the piece attempting to put into practice the valuation. Through filming and watching back the performance I made notes of what I discovered worked effectively and what I felt we still needed to improve or include in the score. I have included this below, with the first list being positive feedback and the second negative:

Lavender and Predock-Linnell discuss the importance of criticism in improvisation, suggesting that the work itself after discussion will always show developments “It is usually not long before unfolding works-in-progress begin to suggest their own possibilities to artists who must then ‘listen’ to these and consider them in light of their own intentions for the piece” (Lavender and Predock-Linnell, 2001, 203). Valuation of the piece after watching it back on video provided means for this too happen. I agree with their idea in that I felt by watching the piece and unfolding it the work began to “speak-back” (Lavender and Predock-Linnell, 2001, 203) which opened my eyes to what could be altered and improved, what was working and what wasn’t. I feel criticism is very important in the development and improvement of a piece of work; to find the faults and highlights.

Continuing with our own scores in the jam was really productive for me, as it gave time for further discussion and valuation in the group to gain more improvements. We began our discussion by going back to our original intention- to create a piece that is interesting. We defined what interesting meant, deciding that it meant unhabitual, different and unusual; we want to create something the audience has never seen before. From reflecting on previous performances we learnt that keeping moments of unison and stillness was effective for our intention as unison and stillness are often hard to find in improvisations. This is due to everyone having their own ideas and intentions within the score that other performers wouldn’t necessarily know. We also acknowledged that thick skinning was still the habitual strategy for creating connections and therefore we would continue to remove this.

A new strategy that we established in the valuation was involving the beginning of the piece. We noted that in general scores begin with separate people, often starting with less people in the space and more join as the work builds. To avoid this we discovered that a more interesting different way to begin would be for all 6 performers to start in a clump together, with some form of contact to another performer, and then to move away from this. This would therefore be the opposite of normal scores. We thought that contact is much more interesting to watch and therefore we would try to create moments of contact throughout, using impulses and finding points where we could create clumps and shapes as a whole group. Starting the piece in this way and including the ‘clumps’ into the work, we felt, would make the movement more distinct and enhance awareness; we would need to be aware if contact was forming and we could physically feel someone touch us to change strategy.

The final decision we made was to remove of the ‘movement makers’. We reflected back on this idea and decided that it wasn’t the best strategy to gain coherence in the movement between the performers. We decided that a more interesting method would be for all the performers to have their own strategy to generate movement. Examples of strategies could be only moving the lower kinesphere, having legs of knives and the upper body being spaghetti or all the cells in the body having a race. At moments of contact in the piece performers would change the strategy they were performing and also change their dynamics. This would keep the piece moving and changing, making it interesting for an audience. We could therefore also use certain moments and strategies to connect with the audience. When watching ourselves performing I found that quite often I lost contact with the audience and would forget to purposefully connect with the audience. De Spain discuses “an increase in energy or intensity when you are in front of an audience” (De Spain, 2014, 61) which is something I would like to discover in my practice, finding ways I can connect with the audience. I feel this would boost my performance as I can use the audience to motivate and energize me, heightening my awareness, strengthen connections and create dynamic in my performance. The constant changing of strategies to something completely new and innovative would remove the predictability of the movement as any strategy could appear at any time.

De Spain, K. (2014) Landscape of the Now. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press.

Lavender, L. and Predock-Linnell, J. (2001) From Improvisation to Choreography: the critical bridge. Research in Dance Education, 2 (2) 195-210.