I found this week’s improvisation the most challenging so far. We aimed to explore composition in space and time, abandoning the security systems usually used to structure time and instead working with felt time. Writing down the part of the reading that inspired me most greatly helped with finding a focus which could be a new starting point for movement. I wrote:

(De Spain, 2014, 109)

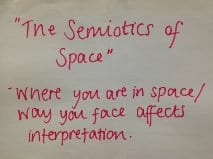

This inspired me due to the idea that you could show the theme or intention of a piece by the placement of the dancer and the way in which they face. I found this interesting as it can either emphasise what the movement is showing but can also change the whole piece and interpretation. I therefore attempted to use this in my improvisations, thinking about what I was trying to show and how the face or position in space would affect this. I could then create movement from this as a starting point.

The first exercise taught me my general habitual tendency’s within space. Through this I found that I generally am much more interested in finding area’s of space that are empty, while I was often attracted to the edges of the space avoiding the middle. I felt the idea of listening to the space was really challenging, due to the fact that the sense of seeing tended to take over. I was influenced greater by what I saw and it was hard to ignore this sense and focus on listening. In this exercise I learnt that I was influenced a lot by other people; I found when others moved I would also, often going to where they had just been. However, this I kept finding that others would have the same intention and that when moving to a space another performer would get there first and I’d have to change my direction and intention.

Through attempting to measure two minutes without the use of a clock and simply trying to feel it taught me that felt time was much different too the clock time. I found that my felt time was much shorter than clock time, feeling like two minutes should have ended much sooner than it did and that the two minutes went slowly. However, in the earlier exercise when told we had 7 minutes but actually taking 19 on a task felt the opposite. The length of time spent felt much shorter than 19 minutes. I found, therefore, that when you are doing something engaging and active the time didn’t go as quickly whereas when you are sat doing very little time was much harder to measure.

The next exercise was the task I found most tough due to needing to distinguish a clear beginning, middle and end. This was challenging due to me not being sure how to make it obvious. I found that habitually I would do a shorter beginning and end section with the middle section longer, suggesting a ABA structure. For me, to make it clear I commonly attempted to make the middle section contrast, often having the beginning and end on the floor and the middle standing or vice versa. My partner pointed out and taught me these habitual patterns, enabling me to find ways to combat them. When I was given the limitation too stay on one level the full time the level of difficulty heightened for me and I was struggling to find different ways to create clear sections. I attempted to change the dynamics for each section while also attempting to alter my habitual timing pattern so that the sections were different lengths. When trying to change the times, I found that they often didn’t change as much as I felt; reflecting back on the idea that felt time isn’t an accurate measure of clock time.

The final exercise we used a score similar to that of Nina Martin. Through this I learnt the importance and difficulty of felt time greater. It was difficult to judge how long each section needed to last for while also keep the set forms of the relationships in the space. This is due to the intentions of dancers being unclear and therefore you may have to suddenly enter or exit the space unexpectedly because another dancer has joint of left. Martin uses this technique in order to develop a “quick thinking on your feet” (Buckwalter, 2010, 62) technique in the dancers as the score “creates dynamic shifts and eventually a flow, as the dancers welcome fast-paced sudden shifts” (Buckwalter, 2010, 62). This helped me in developing these skills but also skills of awareness and engagement, enabling me to notice further what the piece needed and how I could add that. This may have been through me performing a solo and bringing in a new idea or forming a group with other dancers, showing my relationship to them by space and movement developments. The quote from the readings I began with influenced my decisions, remembering that “two people standing close together are linked” and that a soloist upstage can appear lonely yet downstage would invite audiences in (De Spain, 2014, 109). This made me think more carefully about where on the stage I should stand in relation to others and where I should enter and exit.

Buckwalter, M. (2010) Composing while dancing: An Improviser’s Companion. Madison, WI, USA: The University of Wisconsin Press.

De Spain, K. (2014) Landscape of the Now. USA: Oxford University Press.