This week aimed to be even more experimental in the way I used my body, further reducing my habitual patterns. This led to me becoming much more reflective, thinking back to what I had learnt in previous experiments to determine what my habits were and methods we had already explored to combat them. This relates back to what Suzanne Little researched, finding “the key skills/attributes of self-reflection and self-directed learning were highlighted and deemed crucial to the development of well-rounded, independent lifelong learners” (Little, 2010, 38). Here she is claiming that to become a more productive learner, using time autonomously, you would need to have developed these skills of reflection. To begin the experimentation we used imagery in which restricted the movements we did. The images, such as the head being attracted to the sit bones and having knives for legs and spaghetti for arms, disconnected me from the use of habitual movement due to the way that many movements I would usually result back to did not fit within the images created. This meant that I found myself creating completely new movement to fit the image. The final image given (all cells in the body are having a race and are all determined to win) was most influential to my practice. I felt this image pushed me to let go and I found much more freedom as I felt out of control trying to move every part of my body at the same time, engaging even the smaller parts such as fingers. I found that for this I remained fairly upright and stationary due to exploring how fast each part could move at the same time. I experienced a loss of conscious thought and with this came a loss of set codified movement that I would normally show. Creating new movement I have generally always struggled with therefore learning this method was highly beneficial to me. With this theme established, we continued into a solo and I found that this became much slower with falls and I was magnetised to the floor more than I had been earlier. I feel this was due to my body being tired and I would listen closer to what the body wanted to do. I fount that within this solo it was much easier to create and indulge in movement, stretching and pushing my limitations, as all of my body had been made engaged and ready from the image.

Following this, I learnt more strategies but this time to manipulate movement rather than generate it. Strategies such as accumulation, diminishment and retrograde, I found are interesting ways of developing already created movement. In bigger scores, I learnt this could be used to form duos with other performers, avoiding direct copying but still forming a relationship. Creating a duo through manipulation rather than duplicating in a large score was much more challenging due to it being much more difficult to a viewer or performer on the outside of the space to identify the relationships. It often began to look like a selection of multiple solo’s and lots of different ideas with no clear developments and ties between performers. The use of the strategies however persuaded me again to use less habitual movements as it often needed to be related to other performer’s movements without being the same.

I found making this shared choice of movement between performers without communicating through words would emerge through being empathetic towards other performers while also being clear in my intentions. I learnt this from the paper from Monica Riberio and Agar Fonesca they look to find “how communication takes place among dancers during dance improvisation”, finding that it is due to a type of cognition in the body and in relation with the partners (Riberiro and Fonseca, 2011, 71-72). They concluded that “empathy allows the sharing of modes of thinking-feeling the dance so that a group of dancers can decide together when, where, how and which movement to do” (Riberiro and Fonseca, 2011, 82). These results influenced me as in my own practice I attempted to use empathy in order to connect with other performers. This meant I could sense and share other people’s intentions and movement decisions, recognising the means for their choices. Decisions could then be made between us to create effective choreography through improvisation.

The video watched within this session was influential to me in this week’s Jam.

I was inspired by the use of contact and close work, maintaining relationships with others but changing between partners. I experimented with this proximity within the jam through the use of ‘thick skin’. I found myself discovering new ways I could stay close to another person, using the floor and filling the space around them with different arm of leg movements. However, in this practice I found less exploration and that I’d repeat similar movements.

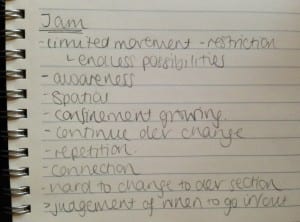

The jam this week was a massive breakthrough for me. I found that for the first time throughout the scores I didn’t think about what I was doing or what step I would do next or what would look most ‘attractive’ to an audience member. My movement suddenly became much less habitual and more flowing, with each movement leading into another and being created in the moment; I felt I spent much less time thinking about what move was going to come next. The main strategy learnt in the jam that led me to this discovery was the use of impulse. This is because and impulse gave a starting point meaning that when a phrase began to run out I could straight away generate something new rather than resulting back to a habitual step.

The rule in the piece that you couldn’t enter made the score more difficult; the score became frustrating because if you found there was something to add to it in the form of a new idea or a development to a current relation you wouldn’t be able to and when you had the opportunity the space was clear and the group were gone. The use of the tide was interesting to me due to you being completely unaware of who was going to enter the space and therefore who you would need to connect with in performance. To me this was a positive as it helped improve my skills of thinking on my feet and dancing in the moment. This also linked to my loss of habitual movement as there was no time at all to plan. The down side to the tide effect was that movement of the tide to clear the space was a group majority decision and therefore you may lose a piece of work you were enjoying.

This jam was massively influential to me. This is due to the changes in the score (adding the tide and not being able to enter the space) while mainly being my sudden discovery in losing habitual patterns. This felt like a great step forward for me in producing work that is original and creative rather than based on codified steps. I hope to continue this further in weeks to come, experiencing and discovering now my limits but also how far I can stretch my ability to overcome limitations to extend my practice.

Buckwalter, M. (2010) Composing While Dancing, An Improviser’s Companion. USA: University of Wisconsin Press.

Ribeiro, M. M. and Fonseca, A. (2011) The empathy and the structuring sharing modes of movement sequences in the improvisation of contemporary dance. Research in Dance Education, 12 (2) 71-85.